|

The Choice – notes

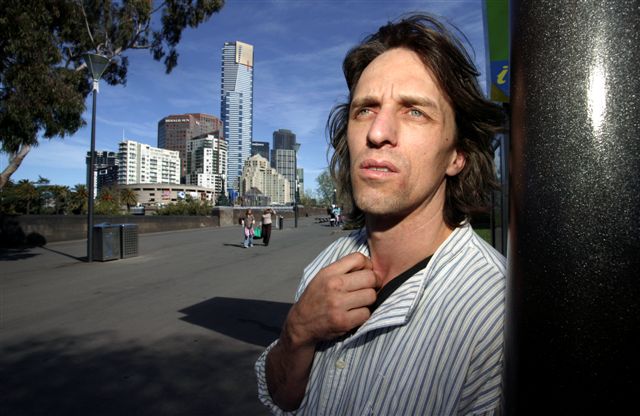

Hiroko with director, Don Parham

Hiroko with director, Don Parham

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT – DON PARHAM

Introduction

It is useful to see ‘The Choice’ , in some ways, as another film in which I explore the subject of relationships between men and women. In this sense, a film about abortion fits neatly into my body of work. It is yet another angle on the same core subject that has underpinned 5 of my 11 films to date. I’ve now put the relationship between men and women under the microscope via films on –

- domestic violence and the gender war (‘Deadly Hurt’, SBS 1994)

- marriage and divorce (‘We’re All Independent Now’, SBS 1995)

- adultery (‘Love’s Tragedies’, ABC 1999)

- men, sex and prostitution (‘Why Men Pay For It’, SBS 2003)

- abortion (‘The Choice’ SBS 2006)

I think it is important to see ‘The Choice’ in this context because some may ask ‘why is a man making a film on a woman’s issue?’ I don’t see abortion as just a woman’s issue for the very obvious reason of the role the man plays in conception. More importantly, it becomes very clear very quickly when you talk to women and men about their personal experience of abortion that relationship issues are usually a central part of the story.

Catarina

Catarina

Where did the idea come from?

Abortion is one of those controversial subjects to which I’m always attracted. I like issues that raise the temperature. When people fight and argue there’s usually something important going on, something worth looking at more closely. The issue of abortion is certainly an example of this. As we have seen in some of the recently revived debates around abortion – eg, debates about late term abortions and RU486 - the heat surrounding this issue doesn’t seem to be in any danger of diminishing.

The abortion issue has been on my radar over many years but I never quite saw an angle for a film on the subject until I came across a book by the Canberra based writer, Melinda Tankard Reist. Titled ‘Giving Sorrow Words’, it is full of very moving personal stories by women who have experienced what is referred to as post-abortion grief. I could see how such stories would work well in a documentary film.

SBS was interested in the idea but they made the valuable suggestion that we shouldn’t limit the discussion only to women who had experienced grief but open it up to a range of experiences, indeed any experience, positive or negative, that women wanted to talk about. SBS also came up with the idea to include men in the discussion, an idea I immediately ran with as a number of my films explore male perspectives on issues.

What happened next?

We knew we had a great idea for a film but we now faced what is always the trickiest part of social issue docos like this – how do we find the people to be in it? I engaged a researcher and we set about finding people willing to bare their souls on national television.

We took a two-pronged approach – advertising plus contacting organizations working in the field. We were careful to approach organizations on both sides of the pro-choice / pro-life divide asking them if they could put us in touch with any women (or men) willing to talk to us. We made it clear that the film was open to anyone of any persuasion as long as they spoke honestly about their own personal experience of abortion.

In the end we didn’t get many leads from these sources, indeed, only one character in the film (Ruth) came from such contacts – the other five coming through newspaper advertisements.

Some comments on the style of the film

(i) The Interviews

From the moment I did the first cut of early test interviews I felt there was something special about the interviews, something I hadn’t quite experienced in any other documentary I had made. I found the interviews instantly absorbing and incredibly moving. Two things struck me –

Firstly, I realised there was probably something special about the subject in itself. Perhaps it was the taboo nature of the subject, the unusualness of hearing people talking intimately about these things for the first time. Whatever it was, this realisation helped me establish a clear vision about the aesthetic for the film. I could see that we should take a minimalist approach, ie we needed to minimise the elements in the film that might distract us from the ‘integrity’ of the interviews. It seemed to me that the interviews could almost be a stand-alone element with nothing else in the film.

Don Parham, Director

Don Parham, Director

Secondly, when shooting the test interviews I had thrown a simple curtain backdrop up behind the subjects and now I thought these backdrops seemed the way to shoot the real interviews. It was one of those situations where something just seems right and it’s only later that you work out why.

I now realise that the curtain backdrops put the characters in a sort of ‘de-contextualised space’ compared with the more usual technique of filming interviews in the subject’s home or office where you pick up elements of their environment in the background. The simple background keeps us focused on the things that matter in an interview – the face, the voice, the body language – things which enhance our ‘reading’ of what people are saying.

(ii) The ‘Cityscapes’

This feeling that the interviews had some special quality that needed to be preserved led me to believe that it would be wrong to intercut the interviews with the usual sort of observational or journalistic style footage of the subjects. We tested this by shooting some material in this way and doing some test cuts. The results were horrible. It seemed clear that the mental space the interviews took you into would be completely destroyed if we took that approach.

I couldn’t believe how much the same words that, in a standalone context seemed so powerful, suddenly became trivial and almost meaningless when housed in sequences full of the usual sort of cutaway shots of the subjects doing this and that around the house. The editor, Martin Fox, and I knew this was not the way to go. The dilemma was that we (along with SBS’s commissioning editor) still wanted to intercut the interviews with some sort of visual sequences … but what?

In time, during the editing process, the idea of shooting the ‘cityscapes’ emerged. It happened alongside the emergence of one of the biggest themes in the film – namely, the conflict our characters felt between what we might call the contrary tugs of the ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ forces in their lives (see below for more on this).

We felt we had to follow our intuitions and take a gamble on the visuals. If we were right that there was something a bit different, a bit unusual about the interviews that might transport the viewer into a more reflective space, then the last thing we would want to do is lurch them back into "reality land". This is what the more typical cutaway footage of the subjects seemed to do. We felt the interviews were impressionistic and worked more like poems and therefore needed to be supported by more poetic imagery. So the idea of the cityscapes began with this and evolved during the early stages of the edit. It happened just as one of the biggest themes in the film also began to emerge from our characters’ stories.

As mentioned earlier, this theme was that the choice they faced revolved around a core struggle. It seemed it was an epic struggle between two ‘primal forces’. On the one hand was the primal life force of pregnancy that was so strongly felt physically, psychologically, even spiritually. Against this was pitted the equally strong primalforce of the expectations, ambitions and plans for their lives. The city - with its vastness and grandeur, its relentless pulsating rhythms, its distractions, its momentum, its march of progress - is a primal force which is equal to, and in competition with, the primal force of new life growing within the person.

This emerged as probably the core drama for our characters. It seemed that giving in to the inner life meant loss of control of the outer life. By interweaving the interview material with the cityscapes we set up a kind of dialogue between the two primal forces, a dialogue which is probably more 'felt' than 'thought' by the viewer.

(iii) Music

The editor had a clear vision about using the music of composer, Helen Mountfort, with the cityscapes. Helen’s music adds a haunting, even mystical quality to the images.

(iv) Captions and the use of silence

In line with the minimalist aesthetic in the film, the decision was made to use captions rather than a voice-over narrator. The intrusion of another voice via a narration would have been jarring and, conversely, the use of silence in the captions enhances the reflective tone in the film.

Catarina with director, Don Parham

Catarina with director, Don Parham

CHARACTERS AND THEMES IN THE FILM

NATALIE

The film opens with Natalie who, in her early 20’s was in a relationship with a man in his late 30’s. She says in the film, “I wouldn’t call it a normal relationship. It was - are we boyfriend and girlfriend? I was never really too sure.” When Natalie fell pregnant her feelings were torn. The relationship didn’t feel right, there were financial issues because her partner wasn’t working and, on top of this, her parents disapproved of the relationship. She says, “there were nights where I’d just cry in amazement and then, half an hour later, I was crying because … I couldn’t find a way where I thought I could keep the child and everything would be great.”

Although Natalie has doubts about the relationship and fears telling her partner about the pregnancy, she is nevertheless astounded by the callousness of his response. She says,

“… He was like ‘well, so when do you make the appointment to get rid of it?’ … There was not even any question for himit was just bang! ‘You’re going to get rid of it, so when do you want to make the appointment?’ … Where I had taken weeksto get where he was, he had taken seconds. It still shocks me now the response – seconds!”

Natalie has the abortion, the relationship never quite recovers, and she moves interstate to start a great new job. She is surprised by her ongoing negative feelings which eventually disrupt her work performance as well. She realises now that she should have spoken to someone instead of carrying the burden alone and that she had underestimated the impact the abortion would have on her. She says,

“There is very little way a woman can have an abortion and just walk away and pretend life is fine afterwards, that nothing ever really happened … A life was inside you. I cannot comprehend how that could happen, and how I thought I was going to be okay, I’m fine. And that’s how I was, ‘how are you?’ ‘I’m fine, fine, I’m fine!’ And then the day comes along where you go ‘you know what, I’m not fine today’.”

Firak

Firak

FIRAK

Next we meet Firak who, describing himself as “a very romantic and idealistic young man” tells us about his first great love. When his girlfriend fell pregnant, the problem was that, although they were very much in love, Firak felt they were too young to have the baby. What’s more, he felt he would be repeating his father’s story if they went through with the pregnancy. His father was 20 and mother 19 when an unplanned pregnancy forced them to marry. As Firak explains,

“My dad probably got himself into a situation too young, and the marriage broke up … I didn’t want to repeat my father’s story, I didn’t want to find myself in that same situation.”

One of the key issues to emerge out of Firak’s story is the role of the man in the choice to have an abortion. Many women talk about men leaving the decision to them, a response that initially appears sensitive and sympathetic, but which in time, they come to see as men washing their hands of responsibility. Firak’ story is an example of another common response of men to an unplanned pregnancy, namely, to put pressure on the woman to have an abortion. As Firak says in the film,

“We probably wanted to have this child, but I really very strongly felt like I wasn’t ready for it. That overrode any other sort of considerations at that time.”

The experience was unpleasant for them both but, as Firak says, the decision to go through with it had its own momentum -

“My vague memory obviously is that she was a bit frightened, maybe very frightened, but it was like these wheels that were moving and we were just doing what we had to do, and our feelings and our emotions, in a way had been put to the side.”

An unusual aspect of Firak’s story is that he and his girlfriend, within a fairly short period, had two more unplanned pregnancies and two more abortions as a result. Firak says that, by the time of the third abortion, “the seriousness of what we were doing and what we got ourselves into came home to me more clearly then.”

As for the impact of the abortions on his girlfriend he says,

“I think it traumatized her, or it was a series of traumas in a way, opening up and conceiving and then having a termination, ripping that life out of her.”

After three abortions, Firak and his girlfriend broke up. Reflecting on the relationship and the abortions, he says -

”We were almost going against the force of our feelings to, for each otherand with each other. Because we conceived, and it was a very powerful thingto do, to do it three times, and the fact that we weren’t able to journeythrough that consciously, to me, I’m quite sad about that.”

At 40, Firak now has 4 children and 3 step-children. He says that he always wanted children.

“Deep down I have a very strong father energy, and my desire to have kids has always been very strong. I remember as a teenager thinking about my kids names, and I wasn’t one of those young guys that’s like - ‘oh I’m not having kids’; that was there, it was so strong in me.”

When asked about how he would respond if any of his children found themselves in a similar situation, he says,

“If a similar scenario happened with my, any of my kids, my sense is that my natural inclination would be that they have the child, that they follow through the pregnancy.”

Firak’s journey seems to have altered his view of abortion from what it was in his early 20’s. He sums up his thoughts on the issue today -

“I mean, I think that the process of conceiving, is a really powerful, it’s a really powerful process, it’s a really powerful event, energy, thing, not to be taken lightly in any way shape or form. And I think that it is more powerful than the thought that ‘this is not a good idea’ or that this is not going to, it’s going to be too hard, I think that it’s more powerful than that. And there is no guarantee, no certainty about where things are going to go in the future anyway, no matter how much you think you plan this or that, so if you conceive, and if you’ve got life in you, I think that that’s incredibly strong to follow that through.”

PAULINE

Pauline was the youngest child in a large Irish Catholic family. She grew up in rural Victoria and, at 17, was sent to Melbourne to do her nurse’s training. She met Ron at a local dance and soon fell pregnant. Pauline says,

“Well I had no idea how a child was conceived. I had no idea that by having intercourse that you could conceive and have a child I just had no idea.”

It was the early 60’s and the sexual revolution and feminism had not yet arrived in Melbourne. Again, the film touches on the theme of the role of the man in the “choice” being made. Ron suggested an abortion to Pauline so she could finish her training. She tells us how she readily agreed -

“I just went along with it. He was my saviour. He was the man that loved me and would do anything for me. Yeah, whatever he said - went.”

For Pauline, the abortion was not a big deal. As she says,

“I just went in and had it. I had an anaesthetic, and woke up and it was all over, and he was there waiting for me.”

Nevertheless, Pauline sees a connection between her relaxed attitude to what she was doing and the more general pattern in her life of handing over control to others. She says,

“I didn’t consider I was going through anything because it was, he said‘you must have it’, and, as I said, I was like this little puppy dog that followedhim around everywhere. I didn’t have a brain, just thinking back to my childhood,I really didn’t use my grey matter anyway at all, to make any decisionsabout my life or what I did, or anything else.”

Ron asked Pauline if they could get engaged on her 21st but, because she was pregnant again, they instead got married on her 21st. Pauline had 3 children in just 4 years. She didn’t want any more but had difficulties with the pill. Pauline raised the question of a vasectomy but, as she so colourfully explains, her pleas were to no avail -

“It wasn’t his problem, it was my problem. I was the one that becamepregnant. That’s when I said ‘well why can’t you have it?’ We were talkingabout the vasectomy, and he said, ‘because I don’t get pregnant.’ No he was aman’s man and nobody touched his crown jewels, just nobody, well I wasallowed to but, yeah, he wouldn’t allow any surgeon to touch them.”

They had a problem.

“Anyway we were careful, right. And that didn’t work of coursebecause Ron would get an erection, and I would be pregnant!”

And that’s just what happened – Pauline got pregnant again with their 4th child but this time she took control of the situation.

“I said ‘we’re just getting on our feet, I’m able to be back at work, we can buy thefew extras, you know like the carpet.’ Even to buy plants for the garden, we used to have to think twice about that when only one wage was coming in and three little ones. So I said ‘that’s it, I’m having a termination’ and he said ‘your decision’.”

Pauline decided to have a termination and tubal ligation at the same time. For her, it was the right choice and she has no regrets.

“I have no, no guilts, whatever other words you can use about theterminations I’ve had. They were done for a reason and - pleased? - I don’tknow if pleased is the word, but I have no guilts about it. Yeah, I did it for me,I did it for the man I loved, and for the last one I had, I did it so that our threechildren wouldn’t be burdened again with another brother or sister.”

RUTH

As a teenager, Ruth was a pretty typical ‘girly’ sort of girl – generally “boy crazy” and having “heaps of fun” as she headed down the beach with her girlfriends. What was less typical about Ruth’s upbringing was that her parents, who were practising Catholics, were actively involved in the Right to Life movement. Ruth was 20 and at uni when she became pregnant to her boyfriend. She admits,

“I wasn’t on the pill or anything like that and I guess we were a bit irresponsible, a bit casual about it, a bit you know, we didn’t think about it as much as we could’ve.”

The shock of an unplanned pregnancy triggered a crisis in Ruth’s life. The values she had been brought up with were suddenly in conflict with the values that underpinned her view of herself as a woman at university and “progressing in her career”. As she explains in the film,

“On one hand I’d grown up being aware of the kind of view that abortionis wrong, or the right to life type of view, where you’ve got the pictures of theyoung babies, and different things, and I’d seen those. All of those sort of things sort of confused me a bit, because I thought ‘hang on, am I going to, on one hand the child is so important and yet on the other hand there’s this kind of pressure to finish my studies and do all those things that a career, that a woman that’s progressingin her career, that’s professional, that’s what have you, should be doing.’So there was a tension there in that.”

Ruth felt the relationship she was in did not have a future. As she says,

“I didn’t have that good a relationship with this guy, we’d been on and off, and it was all, quite difficult at times.”

She decided to have an abortion but, not surprisingly given her background, was torn about the decision. On the one hand she says,

“I guess once I’d made my mind up originally, I was pretty strong willed, I just thought ‘well I don’t really want to do this in a sense, but I have to.”

And then she also says,

“I’d lie in my bed, perhaps during that time, or like the night beforethe abortion and stuff, and just thinking ‘oh my goodness, there’s this..’just this sense I had that there’s this little baby, this little life andthat’s not going to be there tomorrow you know.”

The relationship broke up not long after the abortion and Ruth went straight into another relationship “with a lovely, lovely guy”. After only three months Ruth fell pregnant again but this time the boyfriend said “hey, let’s get married”. Even though the guy this time was more suitable Ruth felt it was premature to contemplate a future with him.

I’d only known this person for three months, I just couldn’t bring myselfto get married … I just thought I can’t, that to me just seemed too soon to makethat kind of commitment, even though I thought a lot of him.”

On top of these obstacles, Ruth was also feeling something a little weirder, as she explains,

“I couldn’t bond to this second baby because I felt like I was missingthe other one … I felt such a sense of ‘I’ve already done the worst thing Icould possibly do by killing the first baby.’ I thought ‘I don’t deserve tohave another baby.’ I remember thinking that at that point.”

Ruth decided to have a second abortion but this time there were signs that she was even more torn about the decision than the last time. She describes an experience she had at the clinic -

“I just remember lying there thinking, I don’t remember feeling pain as such, like physical pain, but I remember being aware of this sort of tugging sensation, and I was quite with it this time, and I just remember this sensation of pressure, and pulling, and thinking ‘the baby doesn’t want to let go, it doesn’t want to let go, it’s really strong, like it’s dad.’ You know strong in character, strong, you know - wants to live.”

Ruth is now 29 and single. She hasn’t had any abortions since the two described in the film. Although she went on to finish her degree and then travel, she says that the memory of the abortions continued to haunt her. After a number of years she sought help from a counsellor. She also re-connected with her faith and sought forgiveness. As part of the healing process she was encouraged by those supporting her to name the babies and her sequence closes with the poignant reading of a letter she wrote to them -

“Dear Grace and David, I wish that you were both really here in this room with me. Here in my life with me. I wish I could see you and watch you growing up, give my love to you. I do love you both. I have been praying that God will show me more what you are like. I believe you are with him and I know that is a wonderful place to be. I’m sure that you are beautiful children, even though I can’t see what you look like. Do you think of me up there, wherever you are with God? It will be so wonderful when we finally get to meet one day. It’s been such a long time. I know that I have asked you this before, but I do ask you to forgive me for aborting you. I’m so sorry. It’s the worst decision I have made in my life. I do hope that somehow we can still have a special relationship, and that I can get to know you in the future. I hope that you enjoy each other’s company and God’s company up there for now. God bless. Love Mum.”

Catarina was the younger of two daughters of Dutch migrants who came to Australia in 1958. As a child growing up here in the 60’s, some of Catarina’s earliest memories are of her parents being absent - working all the time. She says,

“The hard part for mum and dad not only was the language, but theycame out and dad’s qualifications weren’t recognised. Dad wasn’t gettingpaid very well and mum had to work. I mean I was…that sort of era of thesort of mid to late 60’s when I was at primary school, most people had astay at home mother and a working father and of course what I had wasMum had to work 5 days a week and Dad had to work 7 days a week.”

The absence of her parents seems to have been a source of great pain to Catarina, indeed the experience has shaped her attitude to having children ever since. As she explains,

“I can remember being between three and four, before I went to school, and mum had to work, and I was given to friends that they had to look after me, because we didn’t have all the crèches and things, and I know that one time I was sick, and I just remember sort of thinking ‘I just want my mother.’ And she couldn’t be there. And that really made an impression on me. I remember thinking that, and what I made a decision is - if I have children, I’ll be home for those children.”

At 18, Catarina went off to university. She began a serious relationship in her first year at university and, after 5 years, they became engaged. They were both 23 and moved in together after getting engaged. They planned to get married in 2 years - after Catarina had graduated and worked for a year. Catarina fell pregnant not long after they started living together and suddenly all their plans were thrown into turmoil. He wanted to marry straight away and keep the child but Catarina saw things differently –

“My major thing was ‘I can’t do this now’. I would probably resent thechild and the last thing I needed to do was to resent a child as well, it wasn’tfair on a child to bring it into that situation, and I wanted it to have both parents,and I wasn’t feeling sure that it would have both parents. I wanted to be home.If I’d had the child there and then I couldn’t have been home, so the onlydecision to me was to terminate the pregnancy.”

Catarina was starting to have doubts about the long term prospects for the relationship and this made her more determined to take control of her life and not give in to the wishes of her fiancé. She says,

“I blocked everything out. It was – ‘this is my body, my decision, my life and I’m not going to ruin it’. For me to go and have that child was effectively going to ruin three lives, mine, the child’s and my fiance’s, because it just wasn’t the right thing to do and I figured that ruining three lives was not a good thing to do.”

Catarina went ahead with the abortion. For her, the process was straightforward, and without any emotional complications.

“By the time I got out, yeah, I just put it behind me, moved on, went back to uni. It wasn’t easy but it was just something I had to do, I’d made up my mind, you did it, because that’s how you … you move on.”

Catarina and her fiancé started to grow apart and split up two years after the abortion. He quickly married and had a family but Catarina thinks she did the right thing to not have children with him. She says,

“I probably put too high expectations on myself generally. And certainlybeing a mother was high, but it was based on remembering what it was liketo be a three year old thinking ‘I want my mother’, and I didn’t want anyoneelse to feel that lonely. Not rejected, I didn’t really feel rejected, but I justreally wanted my mother. I sort of thought ‘no, I don’t want anyone elseto have to deal with this, it’s not a nice place to be’.”

Over the next 15-20 years Catarina had several long term relationships but none seemed right for having children.

“And of course we were being given that, ‘oh you can have a child, not aproblem, up until you’re 40.’ And I really did want to meet Mr Right andsettle down and have children, and thought ‘well if I can do that in my earlythirties that would be a really good thing, I don’t really want to push it out to35 - 40,’ but you know, I still had to wait for the right person, I wasn’t goingto do it on my own, I wasn’t that determined to be a mother. I’d already made decisions that I was not going to be a single parent. So it wasn’t my be all andend all, but I just assumed I would meet somebody and have a family.”

At 45, Catarina now thinks the opportunity to have children has passed. She sometimes wonders “what sort of mother I would have made, how different my life would’ve been”, but she moves on. At the end of the day, she seems to be ambivalent about the choices she has made -

“You know, I make the best of what I can, I have a niece and nephew who I spend time with, I’ve had interaction with my friends’ children, right through, there’s five of those that I’m sort of ‘aunt’ to. Yeah, that’s the way it is, make the best of what I’ve got and move on. It’s hard, sometimes. Harder than I thought.”

HIROKO

Hiroko was 2 when her family came to Australia from Japan. Her parents established a very successful business here but Hiroko talks about missing her father who was always busy at work -

“I would go to bed, and lie awake and be lying there for quite a longtime and wait until I could hear the sound of my father pulling up in thedriveway. There was certainly a craving for me to spend more timewith him, and to receive more attention, more love from him.”

The marriage of Hiroko’s parents was troubled and she talks about her father’s violence towards her mother. Nevertheless, she felt an acute sense of abandonment when, at 14, she witnessed her father leave the family home, never to return.

“I happened to be the only person that was present at the time when he wasleaving, and I watched him pack up his things into the four wheel drive and hehad remaining about ten boxes left that he needed to carry off. I knew that meantthat I would be nearing closer to his departure. And there was nothing I coulddo. And he knelt down beside me and looked at me and said … ‘be good’.”

On the contrary, Hiroko was traumatised and became a troubled teenager. Two years later, at 16, she ran away to Sydney where she worked as a hostess in a bar servicing the triads. She says of that time -

“I chose to go through a lot of different experiences with men to, I guess, define what receiving love meant, how I could receive love, what kind of love was I worthy of receiving and vice versa, what kind of love was I worthy of giving.”

Hiroko was lucky to survive. At her lowest point she realised she had to get out of there and returned to Melbourne. She was 19 when she began a relationship which led to her first abortion. The relationship was unhealthy at violent at times. Again she knew she had to change things. Hiroko ended the relationship and avoided men for several years until she fell madly in love with a musician. She speaks glowingly of this man -

“He was this amazing, warm character, fun and jovial and giving and caring, nurturing. And he was such a pleasure to be around, and it gave me a sense of trust, being able to trust men again. And that was an amazing gift to receive from him.”

Hiroko became pregnant again and her partner said they should have the child and become a family. Hiroko was 23. She says,

“I was glad in one sense to hear, so grateful to hear that I had someone in my lifewho was so willing and so supportive to be there for me and to be there for the child. And I was also heartbroken because I knew that I couldn’t have the child.”

Competing with Hiroko’s love for her partner and the new possibilities he presented were other values learnt as a child, values which came to the surface at this time -

“He didn’t have a regular income. And I grew up in a family wheremy mother constantly would say to us ‘if you have a family, you needto have someone who’s financially supporting you, otherwise you’llend up being unhappy.’ And I guess that’s what I did believe.”

In spite of many glowing accounts of her partner, Hiroko felt the need to assert her independence as a woman -

“My partner was really quite a special person. He had a lot of qualities in himthat I tremendously honoured in any person and to have and share my life with him was a beautiful experience. But I was not going to make a decision on having the child just to have him in my life. I felt like I needed to be sure that having the child, on my own terms as a woman, as an individual, that that is what I wanted.”

Hiroko went ahead with the abortion. She says,

“That was a decision that I needed to make at the time and that’s what I did.What I learnt from that decision is that sometimes we just do what we need to do,we don’t need to justify it, we don’t need to feel guilty about it.”

Four years later, at 27, Hiroko reflects on her choice. While never saying it was a wrong choice, she seems to regret the loss of something.

“I realise now that if you are with a partner, who is willing to support you, and you’re willing to support them, and share your dreams, and make them come true, then everything else will follow.”

What’s more, she seems to have new insights about how to best manage the twists and turns of life – insights that now have a place for children in the journey …

“I can definitely see that I was choosing to take on a lot of responsibility,and feeling like I had to, almost in a sense, control everything that happened.And having a child is not about that at all. It’s about trusting that that is whatis right and letting go of that control and letting it flower and bloom.”

CREDITS

special thanks to

NATALIE

FIRAK

PAULINE

RUTH

CATARINA

HIROKO

cinematography

KEVIN ANDERSON ASC

(interviews)

DON PARHAM

(cityscapes)

sound recordist

CHRIS IZZARD

editors

MARTIN FOX

DON PARHAM

composer

HELEN MOUNTFORT

production manager

MARTINE DARTNELL

researchers

ROWENA MATHEW

CELIA PARHAM

colourist

ADRIAN HAUSER

Complete Post

audio mix

NEIL MCGRATH

Mixed Media

post production facilities

COMPLETE POST

ROAR DIGITAL

camera equipment

VIDEOCRAFT

stills photographer

DAVID CALLOW

camera assistant

IAN PARHAM

makeup

ANCA DRAGOI

legals

KAREN GOODWIN

Marshalls & Dent Lawyers

production accountant

TONY NAGLE

completion guarantor

JENNY WOODS

Film Finances Inc.

insurances

BRIAN HOLLAND

Holland Insurance Brokers

writer producer director

DON PARHAM

developed with the assistance of

[FILM VICTORIA AUSTRALIA] logo

produced in association with

[SBS independent] logo

commissioning editor

JENNIFER CRONE

Financed by

[ffc Australia Film Finance Corporation] logo

Film Finance Corporation Australia Limited

Parham Media Productions Pty Ltd

© MMVI

* * *

|